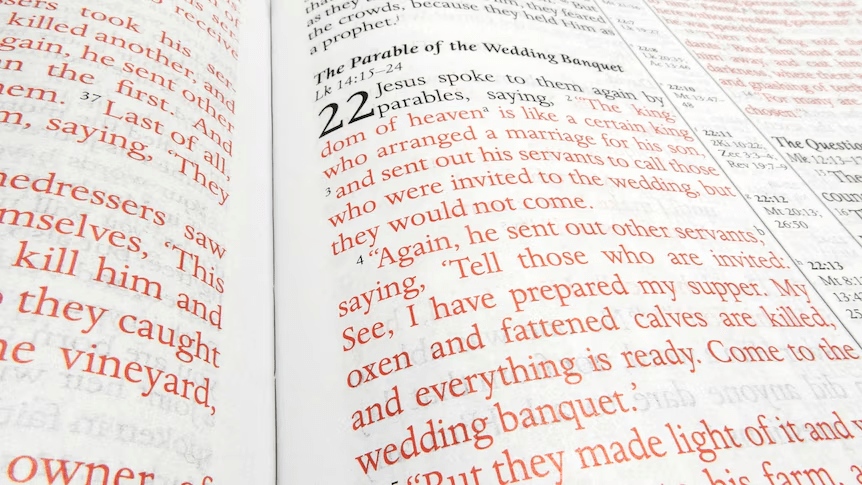

Most English versions of the Bible print the words of Jesus in the Gospels in red letters. It is a tradition that goes back nearly a century. The first red-letter New Testament was published in 1899; the full Bible with a red-letter New Testament was printed two years later in 1901. The reason for this practice is relatively clear, namely to highlight the words of Jesus over against the surrounding narrative and commentary. As noble as this aim is, it can lead to some unhealthy conclusions and applications. Readers might be tempted to conclude that the red letters are more important, more valuable, and more primary than the rest of the New Testament. For example, some so-called “red letter Christians” pit the words of Jesus against the rest of the New Testament and purport to follow the social ethic of Jesus which is characterized by love and compassion rather than the more conservative theology and ethics of the Apostle Paul et al. However, if Jesus is fully God, and there is only one God, and if God inspired the whole Bible, then in a sense all of the words of the Bible, whether black or red, are the words of Jesus.

Of course, this does not mean that the actual content of Jesus’s teaching ministry is unimportant. When it comes to the quest of the historical Jesus, the details of what Jesus said and did are essential for understanding who Jesus was and what he came to do. This is why scholars of the historical Jesus developed criteria of authenticity to determine which sayings in the canonical gospels authentically come from Jesus and which ones do not. Criteria like multiple attestation, dissimilarity, coherence, embarrassment and others like these are used to decide the authenticity of each individual saying or pericope. However, more often than not, these criteria have been used to dismiss more sayings than they have proven. This is most evident in work of the Jesus Seminar and their book The Five Gospels: What did Jesus Really Say? The Search for the Authentic Words of Jesus. Instead of establishing the authentic words of Jesus, they dismissed some 82 % of the sayings attributed to Jesus in the canonical Gospels either as things he definitely did not say (black bead) or as things he did not say but that might be close to his ideas (grey bead). Even sayings that met the established criteria were dismissed as inauthentic. This proves that there was probably another criteria at play in their judgment, that being if a saying evinced a relatively high Christology, then it was not authentic in their view.

More to the point, in my recent book review of Jesus and His Promised Second Coming by Tucker S. Ferda (see here), I suggested that the search for the “authentic” sayings of the historical Jesus in the gospels is a fundamentally flawed endeavor from the outset. This is because the Gospel writers did not set out to record the words of Jesus verbatim (ipsissima verba). They did, however, attempt to convey the words of Jesus by way of summary, thematic arrangement, implication, and interpretation. In other words, they were conveying the essential substance of the words of Jesus as well as it theological significance (ipsissima vox or substantia verba). This is partly because the Gospels are based on traditions that was passed down orally from the time of Jesus until the time the Gospels were composed. Even if the composition of the Gospels is dated early, i.e. in the 40s or 50s CE, then we are talking about 10+ years that have passed from the time Jesus to the time when the sayings of Jesus were written down. The point is that if “authentic” is understood to mean the actual words that Jesus spoke verbatim as he spoke to them, then we are searching for something that will never be found.

On the other hand, we must affirm that the Gospel writers were not simply making things up as they went along, putting words into the mouth of Jesus that he never said or thought. This is sometimes compared to the children’s game of “telephone”, where the first child hears a sentence, and then passes it along to the next child by whispering in their ear, and on to the next and so on. More often than not, when the final child reports the sentence, the final version is a far cry from the original, and usually so horribly garbled as to be beyond recognition. This analogy is a caricature of the actual nature of oral transmission. Not only was the culture at the time of Jesus thoroughly oral, but the Jews in particular took the transmission of oral tradition highly seriously. The Old Testament scriptures commanded them to pass on their faith orally from generation to generation, and Jewish children were trained in this from an early age in the temple and synagogues. The faithful transmission of oral tradition was practically sacrosanct in Jewish culture, and given the recognized authority of Jesus as a rabbi, the gospels writers would never have thought to put their own thoughts and agendas into his mouth. The same could be said for so-called prophetic utterances given by the risen Jesus; these would never have been treated as on par with actual Jesus tradition. As Luke himself indicates in the opening of his Gospel (1:1-4), the Gospel writers were faithfully writing down that which they had also remembered and received.

Now, someone might object, “What about the doctrine of inspiration? Weren’t the Gospel writers inspired by the Holy Spirit and so kept from error?” And I would answer, “Yes! Of course they were!” (2 Tim 3:16-17). But inspiration is not dictation. The Gospel writers were not mindless automatons simply transcribing by rote. Here again, Luke’s introduction indicates that he had done his research, had talked to eyewitnesses, had done the hard work “to write carefully and in order.” In other words, inspiration does not negate the normal processes of research and writing. In inspiration, the Holy Spirit works in, with, and through the human author in such a way that their words are his words. Moreover, the method of inspiration varies according to the genre of the literature being inspired. Clearly, prophetic texts, “thus saith the Lord” were directly inspired speech, but historical narrative, epistles, et al. allow for the creative engagement of the human author with the work of the Holy Spirit. B. B. Warfield puts it this way in The Inspiration and Authority of the Bible,

The Scriptures, in other words, are conceived by the writers of the New Testament as through and through God’s book, in every part expressive of His mind, given through men after a fashion which does no violence to their nature as men, and constitutes the book also men’s book as well as God’s, in every part expressive of the mind of its human authors.

The point of all this is to say that the Gospel writers have faithfully conveyed to us the real and true words of Jesus even if they have not conveyed to us his exact words. So, we should not take individual sayings (or even whole pericopes) out of their narrative context and then dismiss them as wholly inauthentic. This is a fundamentally flawed method of historical and exegetical inquiry. Rather we should attempt to understand how the words and actions of Jesus fit within the context of first century Judaism and how they gave rise to the theology and practice of the early church. As to whether we should continue to print the words of Jesus is red letters, I am of mixed opinion. Further, I suspect that my views on the question will do nothing to unseat standard publishing practice. Nevertheless, we must understand that there is no portion of Holy Scripture that is more authoritative, more valuable, more transformative than any other. Whether we are dealing with the letters of Paul or with the words of Jesus in the Gospels, we are dealing with the Word of God, and it is He who is speaking to us when we read. And so we should ask the Lord to give us the ears to hear and the hearts to receive what the Spirit is saying to us.