I recently read an article about an Oklahoma pastor who is retiring after serving in the same church for 60 years. And let me just begin by saying that this is the kind of pastor that deserves the platform though he would probably never ask for it. So often, we platform the personalities that are the most visible, those pastors who have the largest churches, who have published the most books, who speak regularly on the conference circuit. It would seem we have missed the mark. Our measures of ministry success reflect all of the values and metrics of the world and none of the values of God, who says in His Word that, “Humans do not see what the Lord sees, for humans see what is visible, but the Lord sees the heart.” (1 Samuel 16.7) This pastor exemplifies the kind of nameless faithfulness that is the backbone of Christ’s church; pastors serving tirelessly in insignificant and forgotten places, loving people who are regular and ordinary, proclaiming the Word of God week in and week out. He never published any books; he wasn’t asked to speak at anyone’s conference. He held no denominational influence or power beyond his local association. May his tribe increase!

However, this story is not simply about a pastor who served in the same place for six decades. According to the pastor in question, and I quote, “A lot of it has to do with a church that has kept a pastor for years.” This, it would seem, is the key to long term pastoral tenure; it is churches that keep pastors. A pastor’s theological fidelity and moral integrity notwithstanding, churches bear a God given responsibility to keep the pastors that God has called to care for their souls. (c.f. Hebrews 13.17) According to research, the average pastoral tenure has risen over the years, from 3.6 years in 1996 to 6 years in 2016, but it is clear that the constant churning of pastoral leadership in churches all across this county is at least one major contributor to the weakness of American Christianity. Every pastor I know, myself included, has been hurt by churches who prematurely requested their resignation at the first sign of disagreement, disappointment, or difficulty. Sadly, these stories are often filled with the tears of betrayal, of broken trust, and of shattered confidences.

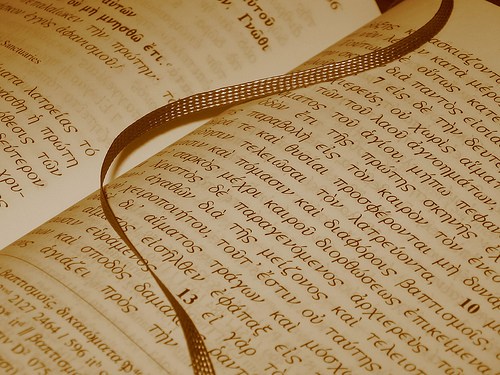

The point is that we need a better paradigm for thinking about the relationship between pastors and congregations. An employer/employee model that is driven by consumeristic expectations fundamentally lacks the virtues of grace that should define the church’s life together. This is why I believe we must recover the biblical idea of covenant, because covenants move us beyond a “what’s in it for me, what have you done for me lately” mindset by forcing us to consider our own responsibility for maintaining the relationship. There are many examples of covenants in the Bible: Abrahamic, Mosaic, Davidic, and New to name just a few. But I would suggest that it is the marital covenant that stands as the closest parallel to the relationship between a pastor and a congregation. Consider the following similarities.

During the “dating” period, the pastoral candidate and the interviewing church put their best foot forward. Both parties accentuate their assets and their strengths and conceal their weaknesses. For the most part, this “get to know you” phase is full of excitement and anticipation of the possible match and its attendant benefits, and each subsequent interaction merely adds to the perception that this is a “match made in heaven.” Both parties wonder if the other might be “the one God intended”. The votes are totaled; the call is accepted. And the relationship moves into the “honeymoon phase”; it is a time that is filled with great idealism and blissful naiveté. Both the pastor and the congregation view each other through “rose colored glasses”; neither party can do any wrong in the eyes of the other. As the relationship grows, every new experience, every new situation is an opportunity to relish in the seeming perfections of the other.

Eventually, however, the difficulties come. The rose petals fall off; the idealism fades. What was once endearing is now annoying; what was once a source of great fulfillment now causes great frustration. Differences in opinion and perspective on all sorts of issues seem nearly insurmountable. The waves of conflict and division threaten to tear the relationship apart, and sadly, in many cases, it does. Marriages end in divorce, and pastors resign, sometimes of their own volition, other times at the behest of church leaders. It is a cycle that is all too familiar, but it need not be so. As in marriage, so also in the church, both parties have a decision to make as to how they will navigate this season. Instead of separation, they can choose to remain committed to each other. They can choose to work through their differences by listening, by showing grace, by compromise. They can persevere and come out on the other side together and stronger for it. Churches can choose to keep their pastors, and pastors can choose to love and serve the church that God has called them to.

This is what relationships should look like within the Body of Christ. We do not give up each other when relationships get hard; we do not throw in the proverbial towel because circumstances are difficult or challenging. We choose love, we choose grace, we choose hope. We covenant together for the sake of the Gospel, for the growth of each other in Christlikeness, for the glory of God. It has been said that most pastors, and I would include most churches, overestimate what can be accomplished in the span of three years, but underestimate what can be accomplished in the span of ten years. So, rather than aiming for some set of five year goals that are ultimately unrealistic, let us strive for that biblical standard of godly faithfulness over time. And when we do this, we can rest assured that we will one day hear those most blessed of commendations from our Lord Jesus, “Well done, good and faithful servant! Share your master’s joy!”

This post was also posted at SBCvoices, here.