A couple of weeks ago, Christians around the world celebrated the death and resurrection of our Lord Jesus Christ. It is a holiday that transcends all denominational lines, theological differences, national borders, language barriers, and time zones. Holy Week. Palm Sunday, Good Friday, Resurrection Sunday, these annual “holy-days” tell the story, that “old, old story, how a Savior came from glory, how He gave His life on Calvary, to save a wretch like me.” It is a time in which we pause to remember, when we focus our reflection, our worship on the good news that makes the Christian gospel unique, timeless, powerful, namely that Christ is risen. He is risen indeed. Each and every day of that week, from Palm Sunday through Resurrection Sunday, is absolutely rich, robust with significance for Christian faith and practice. However, there is one day of that week that is often neglected in the hustle and bustle that usually accompanies preparations for Easter Sunday.

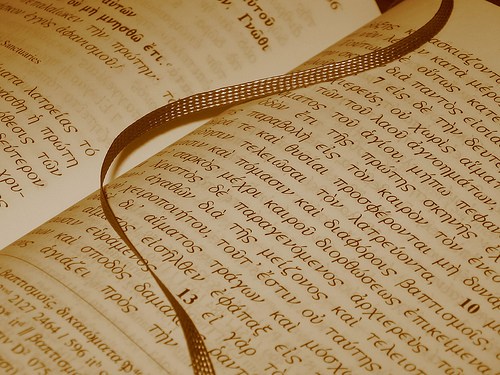

On Thursday evening of our Lord’s Passion, Jesus gathered with His disciples in the upper room. The evening began with a beautiful act of loving service as Jesus washed the disciples feet. This seemingly simple moment subsequently shaped the entire evening as Jesus went on to teach them, saying, “I give you a new command: Love one another. Just as I have loved you, you are also to love one another.” (John 13.34). He then explained that this love would be the primary characteristic that would identify them as His disciples (verse 35). Of course, He would go on that evening to define this love by His own sacrificial death which would occur the following day on Good Friday (John 15.13). This is most likely why he referred to it as a “new command”. It wasn’t new in the sense that it had never been taught; in fact, the OT taught clearly that God’s people should “love your neighbor as yourself” (Lev 19.18). However, the love that Jesus was calling the disciples to that night was something more, something different, something new. This is why we traditionally refer to this day as Maundy, which comes from the Latin mandatum meaning command, “a new command.”

The evening continued around the table as they shared the Passover meal, and it concluded with the passing of the bread and cup, which Jesus reinterpreted as symbols of His body that would be broken and His blood that would be shed for the forgiveness of sins to inaugurate the New Covenant (Matthew 26.26-30). This Lord’s Supper subsequently became central to the worship of the early church. As Christians gathered each week for worship and Word, they would do so around the table; they would share a meal together which would of course include the breaking of bread and passing of the cup (c.f. Acts 2.46). This meal would eventually become known as the Agape Feast or “love feast”, so called after the new commandment that Jesus gave the disciples that Thursday night. It was a time when the followers of Christ could come together to experience the grace of fellowship that is available through the Holy Spirit.

In the modern church, this kind of observance is sadly lacking. Though a few traditions have revived the practice (for one example, click here), for the most part it is widely neglected. We are so caught up in the busyness of our own lives, that we fail to take the time to enjoy the fellowship that binds us together. Even immediate families today barely have the time to share an evening meal together, and when they do, they can hardly be bothered to look up from their screens to interact with one another. But for Jesus and His earliest followers, spending the time to share a meal together around the table was a precious gift of God. Unrushed fellowship over the course of a meal where mutual love to can be shared with one another was foundational in the weekly rhythms of the early church; it was paramount for their life together as disciples of Jesus.

We desperately need to recover this timeless grace, the age old spiritual discipline of table. Of course, this should begin with the weekly observance of the Lord’s Supper as a part of the church’s worship. This ordinance should stand at the center, alongside the preaching of the Word, as we gather together for mutual edification and encouragement every Sunday. It should not be relegated to the end of the service as an obligatory addendum. (For more on this, see my post here.) But it need not end there; it should extend from the weekly worship gathering to homes as brothers and sisters in Christ show each other the grace of hospitality, opening up their homes, sharing meals, loving one another, and doing life together. This is Jesus’ vision for Christian community, that we would love another, even as He loves us, and this is nowhere more on display than we we gather around the table.