One of the primary complaints that is most often levied against modern translations of the Bible into English by the King James Version faithful is that modern translations of the Bible omit some verses. Of course, it is typically the New International Version (NIV) that bears the brunt of these critiques, but the truth is that all modern translations omit some verses that are otherwise included in the Authorized Version (AV/KJV). Surprisingly, that point is actually not up for debate. There are verses that are found in the King James Version of the Bible that are generally not found in modern translations. There are other verses where the text is shortened as compared with their KJV counterparts, and there are still others where words and phrases are modified. The question, then, is not whether there are differences in modern translations as compared with the KJV; rather, the more important question is why there are differences.

And we cannot get too far into the consideration of this question without running headlong in the discipline of textual criticism. However, the problem is that most of the people who sit in the pews week in and week out have very little, or even no, understanding of this important discipline; they have no conception of how the text of Holy Scripture was transmitted from the pen of the original authors to the Bibles that we hold in our hands today. And whether it is due to the negative connotations associated with the word “criticism” or other presuppositions about the way that modern translations came to be, this crucial science is usually met with skepticism, fear, and denial. And this simply should not be.

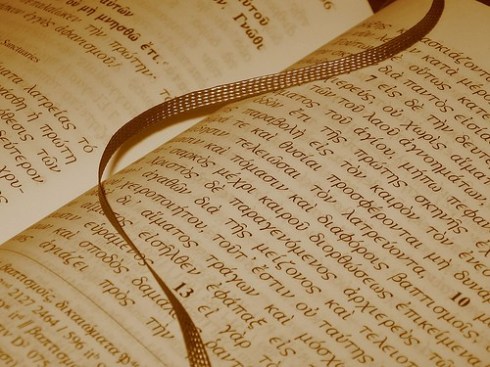

Simply defined, textual criticism is “the process of attempting to ascertain the original wording of a text.” In other words, the Biblical authors of Holy Scripture were the ones who were inspired by God; therefore, it is their words that are the words of God. The challenge, though, for modern translators is that none of the documents that they produced actually exist. These original documents, called the autographs, have passed into the dust of history. Nevertheless, what we do have are copies of those autographs that have been passed down through time, called manuscripts. Of course, before the invention of the printing press by Johannes Gutenberg in the 15th century CE, these copies had to be made manually by the hands of scribes.

Yet, what is perhaps rather obvious but is sometimes forgotten is that these scribal copyists were humans, and as humans, they sometimes made mistakes in the duplication process. Whether in spelling or word order, whether by omission of words, phrases, and verses or by the addition of words, phrases, and verses, the reality is that no inerrant copy of scripture exists. So, when manuscripts from different places and from different times in the history of the church are compared, the truth is that there are incongruities and discrepancies in the manuscript tradition; no one manuscript agrees with every other manuscript in every instance. But this is where the role of textual criticism comes into the discussion. It is the textual critics role to compare these manuscripts with each other, along with evidence from patristic citations and other ancient versions, in an effort to reconstruct the original inspired wording of the Biblical authors.

And the result of this very tedious and time consuming endeavor is referred to as a critical edition. A critical edition represents what textual scholars, after much analysis and research, believe to be the earliest form of the text, the closest reproduction of the autographs, the most accurate reconstruction of the actual words of the inspired biblical authors. This critical edition, then, is used as the basis for translations into other languages like English. Of course, bible translators don’t just take the critical edition at its face value. Where a textual discrepancy makes significant difference in translation, I am sure they analyze the evidence for themselves, but, for the most part, the latest critical edition, usually Nestle/Aland or UBS, is what is translated into English in our modern translations.

Now, going back to the original question regarding omitted and modified verses in modern versions of the Bible as compared to the KJV, the reality is that the KJV, first published in 1611, is not based on the best and most reliable manuscripts that are available today. Of course, for its time, it was the epitome of textual scholarship and translation, but since then, many additional discoveries of biblical manuscripts have been made around the world that are both older and more reliable. Therefore, when there is a difference in the modern translations, rather than jumping to the conclusion that bad people are trying to change the Bible, we must entertain the possibility that they are simply translating a more accurate version of the text.

In the final analysis, the simple fact of the matter is that textual issues cannot simply be ignored in the teaching ministry of the local church. The sheer proliferation of footnotes, asteri, and other such indications in the vast majority of modern translations begs the question as to their meaning and significance. So, whether it is in small group bible studies, e.g. Sunday School, women’s groups, men’s groups, etc., or in the large group preaching/teaching setting, eventually this issue will demand our attention, and both pastors/teachers and members must be willing to have an open and honest discussion about these things.

For further study:

Metzger, Bruce M., and Bart D. Ehrman. The Text of the New Testament: Its Transmission, Corruption, and Restoration. 4th ed. New York: Oxford University Press, 2005.