In my recent posts, I have addressed the use and benefit of the lectionary and of the Christian calendar respectively. I also discussed the season of Lent. Here in the “buckle” of the Bible Belt, these types of discussions necessarily raise the bigger question about the church’s interaction with larger church history and tradition. Given the fundamental roots of most churches in this area, there is unspoken antagonism, or almost hostility, to adopting or adapting anything from the great traditions of church history. We have “no creed but the Bible” as it is often stated. It’s almost as if people believe that there was Jesus and the Apostles and now there is us, and no one has ever tried to follow Jesus in between the two. This kind of attitude leads to a Christian experience that is largely ahistorical, ungrounded, and lacking in any kind of depth or richness. This is easily seen in the lack of definition, conviction, and identity among so-called Evangelicals in the larger American culture.

The bottom line is that every church, every community for that matter, has some kind of tradition, whether formal or informal, whether spoken or assumed. And to act as if this is not so is simply intellectually dishonest. Traditions are the building blocks of culture; they are how culture is passed on from one generation to the next. Without them, ideas, values, and habits would die out and fade away as if they never existed. We are traditioned creatures, and that is not such a bad thing. Traditions tells us who we are and what we value, and they form our identity as members of the community to whom those particular traditions belong.

Of course, not all traditions are good and/or beneficial. There are many examples throughout Christian history going all the way back to times of Jesus or even into the Old Testament where the traditions of men were placed above the commands and teachings of Holy Scripture, where they were used to enslave people and populations rather than lift them up into the godly life. The Old Testament prophets, Jesus himself, and the New Testament authors are all very specific in their critiques of the misuse of traditions. But this does not mean that we may simply disregard them as having no benefit. Even Jesus kept the traditions of His people as an upstanding Jew.

Now, when it comes to the Great Tradition, as it is sometimes called, there are basically three ways we can respond, which are not original with me but are helpful nonetheless. We can reject the parts that are out of date, inappropriate, and/or unhelpful. We can receive the parts that are still good, helpful, and uplifting. Or we can “redeem” the parts that can be useful and beneficial by changing what is bad and reframing what is good. Reject. Receive. Redeem. Or, said another way: abandon, accept, accommodate, but the meaning is essentially the same.

The parts that we reject are easily identifiable, and most, but not all, stem from the Roman Catholic Church, because that was the only church for the first 1500 years of Christian history. So, concepts like those that pertain to the pope or the virgin Mary or purgatory, for example, are all parts of church tradition that we rightly reject. The Reformers were quite specific in their attacks on the traditions of the Catholic Church with which they disagreed. Another example of a tradition that we rightly reject might be John Calvin’s perspective on infant baptism. There is much we can learn from the writings and teachings of Calvin, but we should rightly reject his teaching on that particular topic. There are others, which need not be enumerated, but suffice it to say that some traditions that we see in Church history are temporally bound, specific to a particular people in particular place and time, and these should be respected and understood while not being emulated. Still others are downright unscriptural and should be rejected altogether.

Some parts that we can receive are the historic creeds of the church, e.g. the Apostle’s Creed, the Nicene-Constantinopolitan Creed, the Chalcedonian Creed, and the Athanasian Creed, and the insights from the historic ecumenical councils. There are also plenty of confessions and catechisms that have been passed down through the ages that still hold great value for theological education today. Southern Baptists themselves have their own version of this in the Baptist Faith and Message, first adopted in 1925, revised in 1963, amended in 1998, and revised again in 2000. Another aspect of the Great Tradition that we can receive are the writings of the great figures of church history, especially those that have withstood the test of time. From the patristic era, through the medieval era, the Reformation era, and into the modern era, there have been great Christian writers, thinkers, theologians, and pastors whose teachings are preserved for us in their literary works. As I pointed out above, we do not have to agree with them on every point, but there is still much we can learn from the timeless classics of the Christian faith. This is as true for the pastor, theologian, or professor as it is for the medical doctor, lawyer, grocery worker, or farmer who believes in Christ. If has often been said and it bears repeating that we should spend more time working through old books than we do sprinting through new ones.

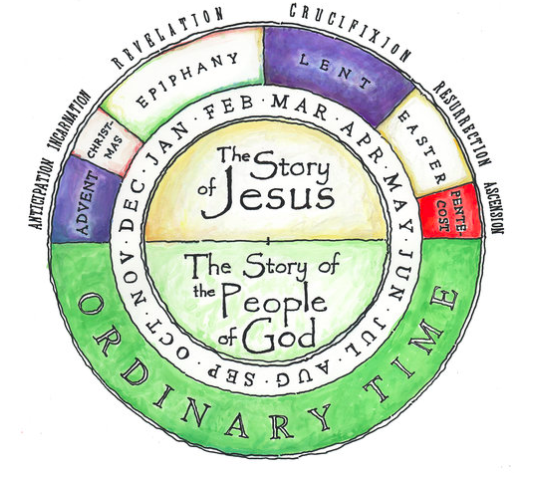

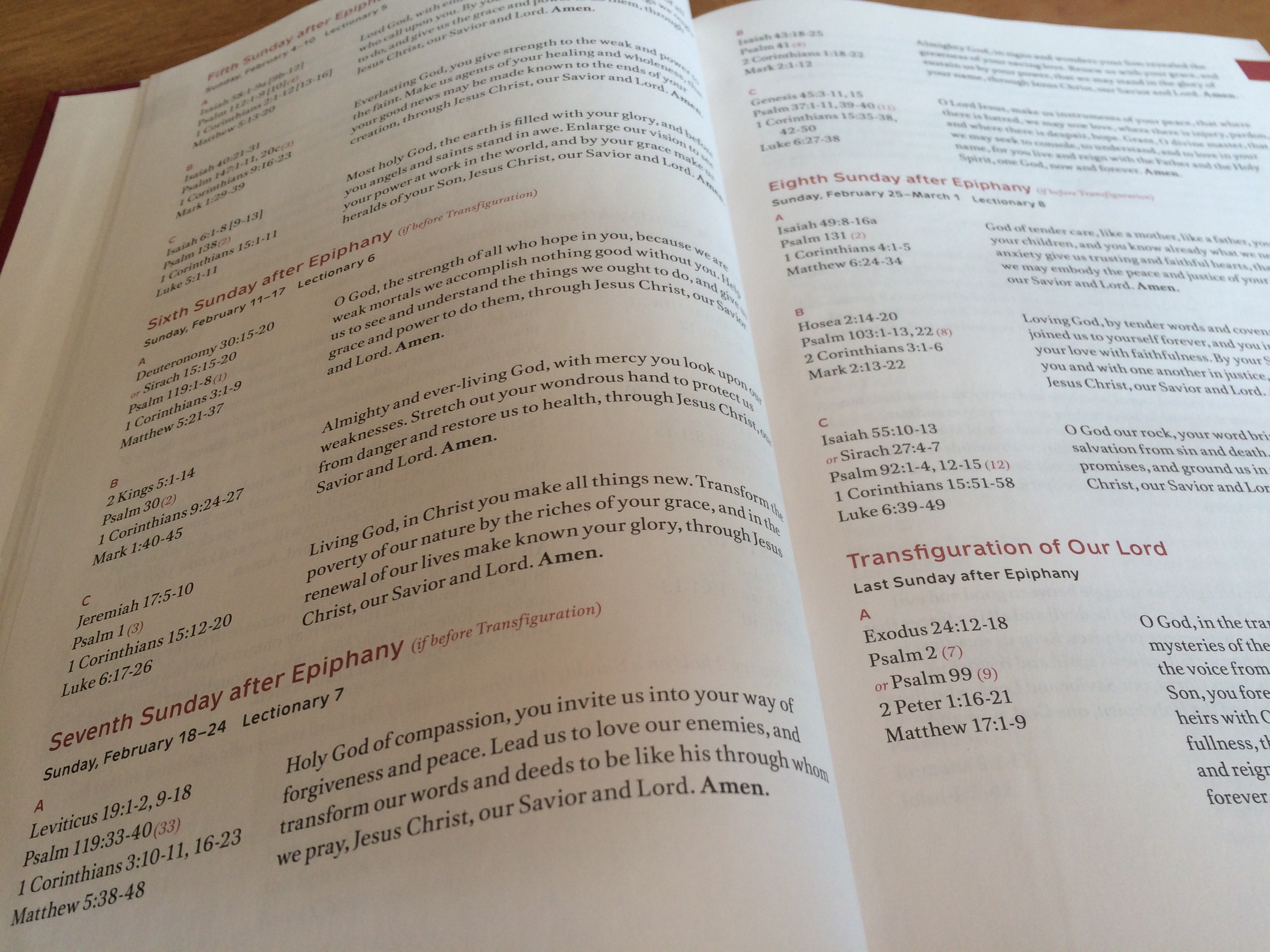

Lastly, some aspects of the Great Tradition that we might redeem include things like the lectionary and the Christian calendar among others. These would fall under the category of devotional and ministry practices, both those for individuals and those for communities. The question of how the Spirit forms us into the image of Christ is not a new one. Faithful Christians throughout the ages have walked the same path of Christian discipleship that we are called to walk today. Certainly the challenges may be different in our cultural context than it was in theirs, but the principles and values have remained mostly the same. We are still called to grow in Christ-likeness, to advance the Gospel in our neighborhoods and around the world, and to love each other as Christ loves us. And we can learn a lot from the beliefs and practices of those who have gone before us.

The Great Tradition of the church is the norma normata (the norm that is normed), and Holy Scripture is norma normans non normata (the norming norm that cannot be normed). Yes, we should hold fast to the doctrine of Sola Scriptura, but we cannot allow that belief to devolve into nuda scriptura. If we can learn to drink deeply from the springs of Christian tradition, instead of isolating ourselves in the now, then I believe that we will find our faith experience to be more enriched and more robust, than what is currently on offer in the Christian culture of today’s churches.

For further study, see:

Williams, D.H. Retrieving the Tradition and Renewing Evangelicalism: A Primer for Suspicious Protestants. Grand Rapids, Mich.: Eerdmans, 1999.

Also updated in:

Williams, D.H. Evangelicals and Tradition: The Formative Influences of the Early Church. Grand Rapids, Mich.: Baker Academic, 2005.