In many ways, the nature of theological discourse, especially when it comes to navigating areas of disagreement, is like a crucible. It very quickly burns away every veneer, every façade, every pretense, and it reveals in no uncertain terms the condition of a person’s heart. It exposes the quality of person’s character in ways that no other interpersonal endeavor seems to. In my last post, I suggested that no matter how stark our disagreements may be, we must still engage our opponents Christianly. We must cultivate the virtues of Christ-likeness even when we are required to address questions of Biblical interpretation about which we hold strong convictions or for which we have the most zeal. Our Lord Jesus Christ is the exemplar par excellence when it comes to interacting with people with whom we have sharp and pointed disagreements, and as His disciples, we would do well to consider His conduct in these matters and do likewise.

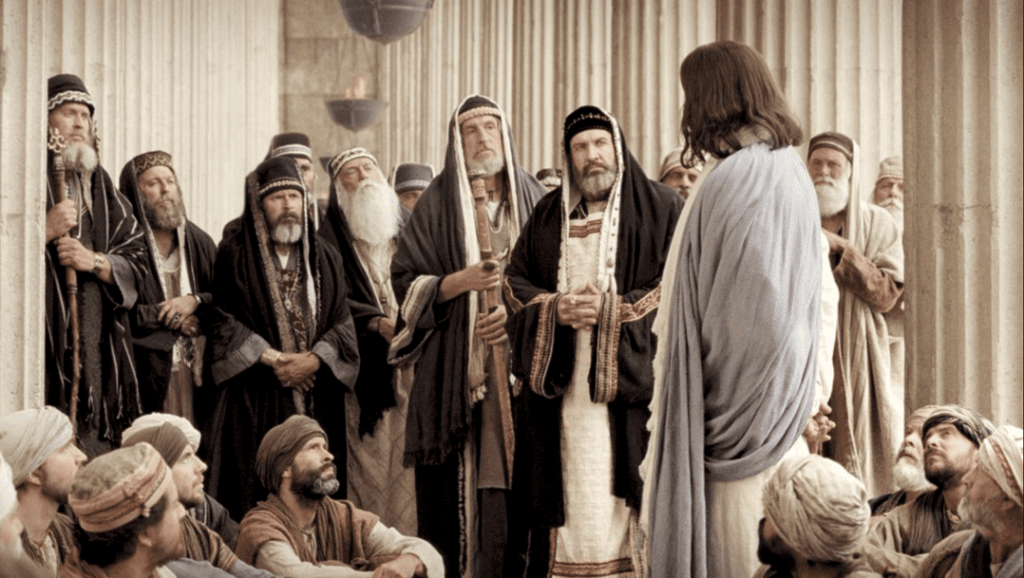

Of course, a cursory reading of the Gospels quickly reveals that Jesus was not afraid of theological debate. There were many occasions where things got quite heated in the discussions that He had with the religious leaders of His day, and Jesus certainly did not hold back in His rebuke of them. He variously referred to them as a “brood of vipers” (Matt 12.34, 23.33), as “hypocrites” (Luke 12.56, 13.15), even as “sons of their father the devil”(John 8.44). To our modern ears, this sounds overly harsh and smacks of contempt. Moreover, it appears to be nothing more than a kind of ad hominem attack, which is a logical fallacy that attacks the person rather than engages the substance of their argument. However, Jesus was a master of language and rhetorical strategy; therefore, He cannot be charged with any kind of personal malice or fallacious argumentation. Upon further study of these exchanges, it becomes clear that Jesus’ disagreements with the Jewish religious were, in fact, quite substantive, and that these disagreements were a large part of the motivations that led the Jewish leaders to plot for His death by crucifixion.

Further reflection on these scenes is beyond the scope of this article; however, the question remains: to what extent are Jesus’ interchanges with the Jewish religious leaders exemplary for our approach to navigating disagreements in theological discourse? Does our pursuit of Christlikeness require that we emulate the rhetorical strategies of Jesus against the Pharisees? Are we supposed to treat our theological opponents with the same attitude and method as Jesus? In answer to these questions, I would like to offer the following thesis: Jesus’ interactions with the Jewish religious leaders of His day are not an example for how we should address our disagreements in modern theological discourse. And in the space remaining, I would like to offer three reasons in support of this conclusion.

First, Jesus had the proper authority to rebuke. The question of Jesus’ authority was the driving force in the majority of His conflict with the Jewish religious leaders. In Mark, chapter 1, and verse 22, we read that the people “were astonished at his teaching because he was teaching them as one who had authority, and not like the scribes.” Jesus possessed inherent authority as Messiah, and this was a direct threat to the Jewish religious establishment. This was the primary point of contention between Jesus and the religious leaders. In fact, the differences in biblical interpretation that separated them were not even that significant by comparison. The religious leaders rejected the messianic claim of Jesus, and that rejection pushed them to conspire for His death as early as Mark chapter 3. So, in truth, the conflict between Jesus and the religious leaders was never really a theological one to begin with. It was through and through a question of authority and submission, specifically the messianic authority of Jesus and the refusal of the Jewish leaders to submit to Him. Therefore, we must conclude that the rebukes that He spoke against them were aimed, not at their theological disagreements, but rather, they were meant to provoke the religious leaders to repentance and submission.

Secondly, Jesus had the necessary character to rebuke. We confess that Jesus is the second person of the Trinity incarnate, fully God and fully man, born of the virgin Mary, born without sin. He was “tempted in every way as we are, yet without sin” (Hebrews 4.15). He lived a sinless life in perfect obedience to the Father. He was not given to vices like pride and arrogance, contempt, scorn, guile, etc. Even in His anger, He was without sin. This means that the rebukes that He levied against the Jewish religious leaders came from a heart that was perfectly righteous and holy. He was genuinely driven by love for God and by love for His opponents; He championed the truth for the sake of the truth, not for personal gain or one-upmanship. His motives were never mixed, never polluted, never turned toward self, but always meant to bring His opponents to repentance and faith. This is the ideal to which we must aspire; however, on this side of glory, we can never be certain that our motives are perfectly pure. As long as we live in this fallen world, our attitudes will necessarily be mixed with sin, which is why we be ever conscious, always examining the motives of our hearts before venturing to rebuke those with whom we disagree. We should submit ourselves to the examination of the Spirit, praying as the psalmist taught us, “Search me, God, and know my heart; test me and know my concerns. See if there is any offensive way in me; lead me in the everlasting way.” (Psalm 139.23-24)

And lastly, Jesus had the ideal context to rebuke. It goes without saying that the world has changed since the days of Jesus and His first followers. His was a culture that was primarily oral, where theological discourse was a public affair, where disagreements were hammered out in face to face dialogue in front of a crowd of onlookers. By contrast, ours is a culture that is primary literary, where theological discourse is a written affair, where disagreements are hammered out in books and journal articles that are subject to peer review and the editorial process. Of course, the proliferation of social media has all but circumvented those processes; avenues for both formal and informal review are nearly nonexistent in the facebook realm, the twitterspace, and the blogosphere. But there is a big difference between discussing our theological differences in face to face conversation and taking anonymous potshots from behind a computer screen. When Jesus launched His rebukes against the Jewish religious leaders, He was operating in a open and public context that required active listening and clear argumentation. It was a context that had natural checks and balances in the form of the watching crowds. He knew His opponents, and they knew Him; there was no hiding. The point is this: context matters. In other words, context determines how we navigate our theological disagreements. How we discuss these matters in face to face dialogue is very different from how we handle them on social media or in the pages of published scholarship.

In conclusion, there is a vast difference between the rebukes that Jesus levied against those who had rejected Him as their Messiah and navigating our theological disagreements within the body of Christ. And what we must affirm is that Christians are called to navigate their disagreements with attitudes and approaches that are counter to the ways of the world at large. We are called to be different, we are called to righteousness and holiness. We are called to the way of love. It is natural and easy to love those with whom we agree, but it is whole other challenge to love those with whom we disagree, even when that disagreement is relatively minor. We must learn to love others theologically. The example of our Lord Jesus Christ demands nothing less than this.

For further study:

Smith, Brandon D. “Loving Others Theologically”, posted at mereorthodoxy.com, July 10, 2018.