Every church has a calendar, and by that I mean that every church has an annual rhythm of seasons that defines their corporate life together. Every year, churches tend to observe the same set of holidays, seasonal emphases, remembrances, and milestones. Now, in most low church or free church traditions, especially here in the “Bible Belt”, these annual rhythms are usually indistinguishable from the civic, cultural, and sentimental holidays celebrated in the larger culture, so, in the final analysis, we would have to acknowledge that this type of annual calendar cycle is not distinctively Christian.

We celebrate our American civil and patriotic holidays, like Independence Day, Memorial Day, Veterans Day, Flag Day, or Presidents Day. We remember the Hallmark holidays, like Valentine’s day, Mother’s Day, Father’s Day. We even commemorate holidays for history and heritage, like Halloween, Thanksgiving, , Columbus Day, or Martin Luther King’s birthday. And these are not bad or wrong things to remember or celebrate; they are unique to our cultural and historical identity, but, are they making us more like Christ? By marking our year by this calendar, are we growing in our understanding of the person and work of Jesus, and are we conforming our identity and values to his?

Of course, there are two Christian holidays that we celebrate every year, those being Christmas and Easter. However, it seems their Christian meaning often gets lost in the unbridled consumerism of our culture. These historically Christian holy days have become more about Santa Claus and the Easter Bunny, Christmas trees and other seasonal decorations, exchanging gifts, egg hunting, and having holiday parties, and their Christian significance is relegated to a 1-2 hour Church service, if that. So, is there a way to reckon our yearly and seasonal cycles in a way that is more centered on the person and work of Jesus Christ? Is there a way to move the Gospel from the periphery of our remembrances, our celebrations, and our commemorations to the center of them?

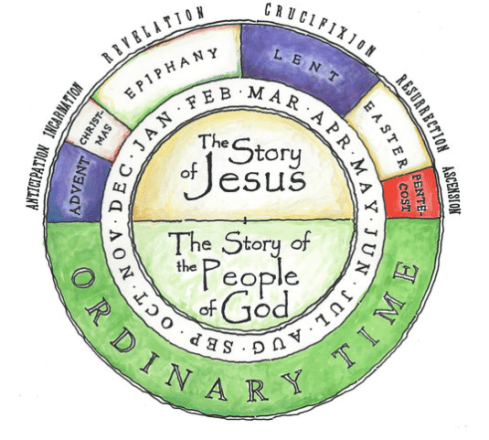

I would submit that there is, and I would also submit that the church has been following this annual seasonal cycle for the vast majority of its existence. For most of church history, Christians all over the world have followed the Christian calendar or the Church year. This is a calendar that begins four Sundays before Christmas with the season of Advent, proceeds through the seasons of Christmas and Epiphany, continues through the seasons of Lent, Holy Week, Easter, and Pentecost, then ends with the celebration of Ordinary Time which climaxes on Christ the King Sunday. This annual celebration of the Gospel focuses our celebration, remembrances, and commemorations on the person and work of Jesus Christ, and as we repeat it every year, it forms us more and more into his image. It conforms our values, our priorities, and our perspectives to those of the Kingdom of God.

This is what might be called the spiritual discipline of time. Richard Foster has the best definition of spiritual disciplines in his book Celebration of Discipline: The Path to Spiritual Growth. He describes the spiritual disciplines as a way of assuming a posture of submission within which God can do his sanctifying work. In other words, they are God’s way of putting us where God can work within us and transform us. The Disciplines can only get us to the place where something can be done; they open the door to life in, with, and through the Spirit.

And the need for a spiritual discipline of time has never been more pressing than in today’s fast paced instant gratification seeking culture. In our world, we do not know how to wait for anything. We rush from one experience to the next hardly allowing the time and space necessary for the significance of those experiences to soak into our souls. The seasons of the Christian Calendar force us to slow down and to sit in the grand narrative of Gospel of Jesus Christ week after week, Sunday after Sunday.

In the final analysis, the holidays and occasions that we choose to remember reveal our true values and priorities; they tell a story that reveals the most fundamental realities about who we understand ourselves to be. As Christians, our identity is to be grounded in and conformed to the identity of Jesus Christ. We are Christians first and foremost, and all other claims that attempt to form our identity must come second. Observing the Church Year tells the story of Gospel as the controlling narrative for who we are and what we are called to do, and as we cycle through it year after year, we hopefully move deeper and deeper into it’s mystery. May we rediscover this historical discipline as we seek to be made more and more into the image of Christ.

For further study, see: Emerson, Matthew Y. On Objections to the Church Calendar. The Center for Baptist Renewal, posted 2.15.18.